Reposted from the Hartford Business Journal

by Joe Cooper

Urban League of Greater Hartford CEO David J. Hopkins said job training and workforce development programs will be increasingly important as minorities have been hit hardest economically by COVID-19.

From late March to early August, Capital Workforce Partners’ (CWP) new call center received some 6,000 inquiries from people wanting help with resume and cover-letter writing, and finding employment opportunities.

The significant demand for job-placement assistance reflects the negative impact coronavirus has had on Connecticut’s economy, where the official 10.2% unemployment rate is believed to be much higher.

But it’s minority populations in particular that are being hit hardest by the pandemic’s economic fallout, labor data shows.

So, as more focus is being placed on racial equality amid the nationwide Black Lives Matters protests, Black and Hispanic populations are actually falling further behind economically in Connecticut because they’re employed at a higher rate in industries most impacted by COVID-19.

Hartford area nonprofit leaders, particularly those focused on workforce development programs for minorities, and others say state lawmakers must do more in the upcoming legislative session to address the widening economic disparities among racial groups.

Until that happens, however, nonprofits are being relied upon — even as their funding streams remain under intense pressure — to address job-readiness gaps exacerbated further by the pandemic.

“We never stopped [providing our services] because the people need us more than they ever have,” said Kimberly Staley, chief administrative officer of Capital Workforce Partners, a workforce development board that connects people to career training and job-placement opportunities.

Volunteer Elena Goodman approaches a car in line for a drive-through food pickup at Foodshare at the Hartford Regional Market, Wednesday, April 15, 2020. Foodshare distributes food here Monday, Wednesday and Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. to provide food to those in need during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Minority populations have been hit harder economically from the start of the pandemic.

During the first two months of the health crisis in the state, 14.5% of African-Americans and 13.9% of Hispanics filed for jobless benefits, compared to 11.2% of white residents, according to unemployment claims data. That’s likely a result of minority populations, labor data indicates, occupying at higher rates jobs in the retail, hospitality and food services industries, which were slammed by COVID-related shut downs.

Additionally, almost 23% of Connecticut’s Native American residents filed for unemployment during that period as Mohegan Sun and Foxwoods Resort Casino temporarily closed in April and May.

The contrast among racial groups is even more apparent when looking at municipal unemployment statistics.

In Hartford, where 38% of residents are Black and more than 45% are Hispanic, the unemployment rate stood at 17.6% in July, according to the state Department of Labor (DOL). The jobless rate in other cities with a larger percentage of Black and brown residents was 11.8%, 15.1% and 15.2% in New Haven, Waterbury and Bridgeport, respectively.

Those numbers are well above the state’s overall 10.2% unemployment rate.

Connecticut’s economy is being hit hard by the pandemic because the state over the last decade added many low-wage jobs that are susceptible to the health crisis, according to UConn economist Fred Carstensen.

That trend accelerated with the onset of the Great Recession.

A 2019 report by the Office of Policy and Management found that Connecticut over the prior decade lost a net 45,400 jobs in higher-wage industries (insurance and finance jobs that pay in the $70,000 range), while it gained a net 10,000 positions in lower-wage industries (hospitality, logistics and tourism sectors that pay in the $30,000 range).

“Connecticut has become the Florida of the Northeast, with a concentration on hospitality, tourism, elder care and logistics,” Carstensen said. “And the nature of those jobs is, you can’t do them from home. They are contact jobs, so it’s a double whammy.”

Workforce recovery initiatives

Workforce development needs to be a key focus for lawmakers in the upcoming legislative session, Carstensen and others say.

The state does have worker training programs, but they are limited in the number of people they serve, Carstensen said.

As a result, many nonprofits have been relied upon to fill the gap, but it doesn’t make for a robust, coordinated strategy.

CWP is one of the few workforce development groups in Connecticut eyeing a regional approach to upskilling and retraining underserved populations.

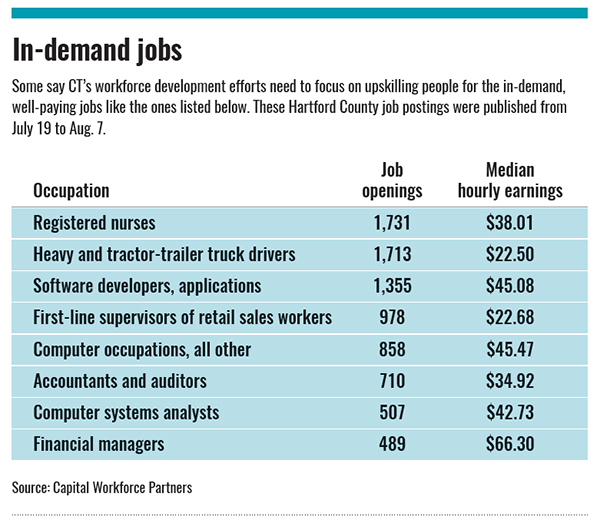

In-demand jobs in Hartford County.

But the task won’t be easy because of academic achievement gaps in the state, and the fact that 65% of jobs in the next few years are going to require post-secondary education, leaders say.

Meantime many low-wage positions that disappeared during the pandemic may never return.

In Hartford, only 25% of students on average earn a post-secondary degree, and less than 40% of seniors in the city’s public school district this year have a complete post-secondary plan, CWP data shows.

CWP is aiming to address low literacy rates and skill shortages, in part, by leveraging $3.6 million in funding from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The money, CWP Chief Strategy Officer James Boucher said, will be used to provide new training opportunities in manufacturing, health care, IT, construction, finance and transportation for mostly individuals of color ages 18 to 24. That group, commonly referred to as “opportunity youth,” includes individuals who are typically out of school and out of work.

CWP is also collaborating with the Governor’s Workforce Council as it updates the state’s strategic job creation plan, which could be aired sometime this fall.

“We are hoping that there will be continued significant investments for reskilling, training and technology supports for workforce boards and industry partnerships that are considering the issue,” Boucher said.

Meanwhile, the Urban League of Greater Hartford is using new federal funds to provide job-training opportunities for those re-entering the workforce from the criminal justice system.

In partnership with Hartford’s Capital Community College, CEO David J. Hopkins said the Greater Hartford Urban League will use $410,000 in funding over the next three-plus years to upskill individuals for jobs in construction, nursing, medical services and warehousing, among others.

“While college might not be for everyone, we think education is,” he said. “We are trying to give people an employable skill with documentation to show they are qualified and get them into positions.”

Elizabeth Horton Sheff, director of community programs for Hartford nonprofit Community Renewal Team, says the problem with nonprofits overwhelmingly leading job readiness efforts is that they operate on grants for a specific, limited service.

For example, CRT’s federally funded YouthBuild program is one of a few initiatives the organization provides to accelerate youth job training. The program, meant for teens and young adults ages 18 to 24 from the Hartford area, often leads participants to careers in construction or health care. But the funding is not reliable over the long term, she said.

And many nonprofits are seeing revenue streams dry up amid the pandemic.

“The other obstacle is things they might need, like a tool belt, books or transportation,” Horton Sheff said. “How do we pay for that? And how do we get those resources to them?”